A matter of life and death: Islamic Organization for Food Security kicks off multiple programs in pursuit of zero hunger

This article is part of a series sponsored by the Islamic Organization for Food Security (IOFS).

How do you solve a life and death issue like hunger?

Yemen is heading toward the biggest famine in modern history, said the U.N. World Food Program Executive Director David Beasley after a visit to the country at the beginning of March.

“I was in Yemen, where over 16 million people now face crisis levels of hunger or worse. These aren’t just numbers. These are real people,” said Beasley.

He believes that without urgent intervention around 400,000 children may die there this year. “Are we really going to turn our backs on them and look the other way?”

Yemen faces an ongoing political conflict as well as severe agricultural challenges similar to other Organization of Islamic Cooperation (OIC) member states.

The country suffers from a range of issues including low agricultural productivity, water scarcity, and lack of infrastructure facilities and production technologies, says the U.N.’s Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO).

It is one of the populations that makes up the 176 million people in OIC countries battling acute hunger and malnutrition, according to the Statistical, Economic and Social Research and Training Centre for Islamic Countries (SESRIC).

This substantial number accounts for around 10.5% of the OIC’s total population, despite the 57 member states managing more than enough arable land to feed themselves—some 1.38 billion hectares, equivalent to more than a fourth of the world’s agricultural area.

For the OIC, enhancing food security means increasing edible production to make food more available, accessible, and affordable.

The journey on the roads to fulfilling these goals is gruelling and overwhelming but not entirely defeating.

Taking the bull by the horns, in 2016 the OIC inaugurated the Islamic Organization for Food Security (IOFS).

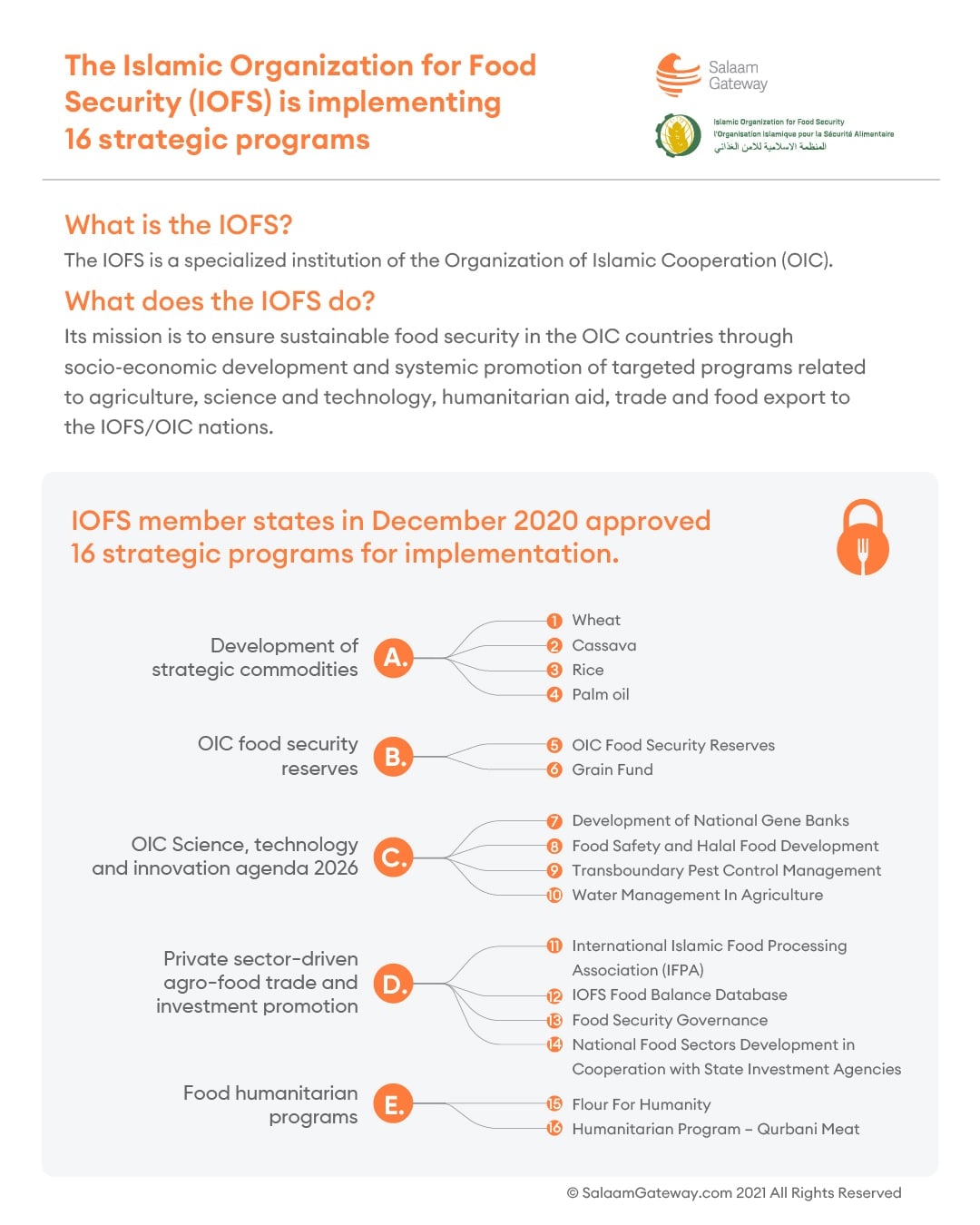

After a period of careful and painstaking planning, IOFS is now ready to implement 16 strategic programs that were approved at its third General Assembly in December last year.

The organization will address the persistence of hunger by boosting food availability and accessibility, while championing supply stability.

THE NEED FOR IOFS

“We believe that the food we consume needs to be nutritional, safe, halal and enough for everybody,” IOFS Director General Yerlan Baidaulet told Salaam Gateway.

“Unfortunately, many of our countries are very fragile and vulnerable due to different kinds of problems like natural disasters such as droughts and locust invasions or political conflicts.”

Led by Baidaulet since August 2019, the IOFS operates as a joint OIC body to strategically increase food security, strengthen fragile food systems and improve livelihoods across all member states.

It has four main objectives: sharing technical know-how and expertise across the OIC member countries, monitoring and assessing food security patterns, managing and mobilizing financial and agricultural resources, and coordinating, formulating and implementing standard agrarian policies across the bloc.

Currently, 36 OIC member states have signed the IOFS statute. The most recent ones–Morocco and Tunisia–joined this year.

Headquartered in Kazakhstan’s capital Nur-Sultan, the organization is financed through membership fees and voluntary contributions, in addition to grants from the Islamic Development Bank.

Major projects range from the development of strategic commodities wheat, cassava, rice, and palm-oil, to the establishment of the Islamic Food Processing Association (IFPA), to elaborating a regional mechanism for the Food Security Reserve, and the establishment of a Grain Fund.

Other flagship projects include a workshop on the development of National Gene Banks and a roundtable on increasing water use efficiency in the agricultural sector.

AVAILABILITY: FOOD FOR MILLIONS AND MILLIONS

A key raison d’être for the very existence of IOFS is that food availability poses a constant challenge for OIC member countries.

Of the 34 countries in Africa and nine in Asia that currently require external assistance for food, 23 are OIC nations.

Among these, 16 million people in Yemen, 13.15 million in Afghanistan, and 12.9 million in Nigeria need urgent help. In Syria, about 12.4 million, or 60% of the overall population, are food insecure.

Making food available for these tens of millions means providing enough sustenance either through domestic production or imports.

But domestic production of food among OIC countries has been falling. The share of agriculture in OIC countries' total GDP gradually declined from 11.3% in 2000 to 9.8% in 2018, according to SESRIC. The drop is caused by environmental stresses, structural transformations, and agricultural market instability.

Where there are shortfalls of food supply, they were filled by expensive imports. This threatens the affordability of food. Organizations such as the International Islamic Trade Finance Corporation have been helping OIC countries in this regard. For example, in 2019, it funded the import of over 1.3 million tons of wheat and 260,000 tons of rice, benefiting OIC nations such as Egypt, Comoros, Mali, Burkina Faso and Tajikistan.

To boost food production and develop strategic commodities, IOFS established the Centers of Excellence for rice and wheat.

“We have carefully planned to establish key Centers of Excellence to cover most of OIC geographic regions,” Baidaulet said, adding that the centers would use the latest digital technologies to guarantee superior performance.

The centers serve as platforms for capacity building, knowledge sharing, and experience exchange between academia from member countries.

The development of the rice industry, for example, needs advanced and innovative solutions, said Baidulet.

Rice cultivation in the OIC region accounts for around 23% of total world production. 90% of the world's rice production and consumption occurs in Asia, according to IOFS. Other than China and India, Islamic nations Indonesia and Bangladesh are also big producers.

Outside of Asia, Egypt has huge potential to grow rice.

“Egypt is endowed with some very good production areas along the River Nile, and they are getting high yields of rice and wheat,” soil scientist Dr. Bashir Jama told Salaam Gateway. Jama is the former Lead, Global Practice, Food Security Specialist at the Islamic Development Bank.

“They're using science and technology and good irrigation systems,” Jama said, adding that the Nile basin grounds are parallel to those in Europe – alluvial and thus rich, organic soils.

But soils and crops aren’t the only concerns for food security.

There are other opportunities, such as investing in local manufacturing and agriculture through public-private partnerships, that will boost both food security and economic growth while reducing reliance on imports, according to the latest State of the Global Islamic Economy Report.

Taking the concept of private sector development to heart, later this year IOFS will officially launch its first subsidiary - the International Islamic Food Processing Association (IFPA).

“The International IFPA is a global platform for future interaction between entrepreneurs and all stakeholders in the entire ecosystem,” Baidaulet explained.

The new association will support small and medium-sized agri-food producers to penetrate intra-OIC markets. Its work will help to increase export revenue through value-added industrial processes and attract inward investment in the food value chain.

Photo: The flags of the member states of the Islamic Organization for Food Security at the Nur Sultan, Kazakhstan, headquarters.

ACCESSIBILITY: WORSENED BY PANDEMIC AND CRISES

IOFS Director General Yerlan Baidaulet describes 2020 as a “disaster” for food security.

The effects of the COVID-19 pandemic exacerbated food security vulnerabilities and resulted in increased humanitarian needs.

If the pandemic wasn’t enough of a struggle, the situation became even more dire as miles of swarms of locusts destroyed crops in eight countries in the East African region, and Pakistan and Iran in Asia.

IOFS estimates the loss of crops and livestock at a crippling $15 billion.

To guarantee access to food in times of crises, IOFS invited member states to consider the creation of an OIC-wide Food Security Reserve, a critical program to ensure collective food security and effective humanitarian emergency response.

The organization has finalized a pre-feasibility study to establish regional food reserves, aiming at providing the populations of the OIC member states with a sufficient amount of sustenance in emergencies.

The program underpins the philosophy of Islamic Solidarity, and will facilitate scaling up the intra-OIC “South-South Cooperation” in terms of humanitarian aid interventions.

As part of these efforts, the Grain Fund was presented as a basic element of OIC Food Security Reserves, which is based on Islamic forward and takaful transactions.

IOFS envisages public-private partnerships can kickstart the program.

It suggests the use of Islamic financial instruments, including sukuk, to finance the infrastructure construction for the food security reserves.

CHALLENGE: COMPETING SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT GOALS

The IOFS may already have the considerable responsibility of tackling food availability and accessibility but it must also do so while balancing competing SDGs.

Food systems are responsible for a third of global anthropogenic GHG emissions, according to Crippa et al. in the March edition of the research journal Nature Food.

At the same time, climate change represents a threat to food supply.

Major crop yields across Africa and South Asia may decline by 8% by 2050 as a result of climate change, says Jonathan Mockshell and Eliza J. Villarino in the Encyclopedia of Food Security and Sustainability.

“Agriculture's footprint and climate change are a global concern,” confirms Dr. Bashir Jama.

Indeed, apart from farming and harvesting, food also requires processing, packaging and distribution before it is cooked.

The entire supply chain triggers the emissions of anthropogenic greenhouse gases (GHGs), and consumes a lot of energy.

Rice, a leading food crop, is a principal source of CH4 emissions. In Bangladesh, for example, the share of rice production to total food system emission amounts to a substantial 40%.

In eastern and western Africa, where mostly smallholder farms are responsible for food production, the shares of land-based food system GHG emissions accounted for 88% and 69% in 2015, respectively.

The challenge, as pointed out by Jama, is to ensure that agricultural production is sustainable and not environmentally degrading.

HOW DO YOU SOLVE THE LIFE AND DEATH ISSUE OF FOOD SECURITY?

The issues of food security are complex, often inter-connected, and can easily overwhelm.

IOFS has a very big job on its hands as it starts implementing 16 programs this year in its pursuit of zero hunger.

How will it succeed?

The answer lies in partnerships.

“You can be rich, you can be wise, you can have everything. But acting autonomously won’t get you results,” said Baidaulet.

“Only by working together in a partnership with the governments, with the people, with international institutions, can we achieve results.”

© SalaamGateway.com 2021 All Rights Reserved