Are charitable organizations in the West leveraging Zakat?

Walk through any high-street fundraiser in London or scroll a U.S. appeal page during Ramadan, and you won’t be wrong in concluding that Zakat is a fairly well-known and leveraged option in the West.

The real answer to whether this is surface-level branding or whether mainstream charities in the West have retooled their fundraising, governance, and programs to unlock Zakat at scale is a bit more nuanced.

Even as a growing cohort of major humanitarian organizations has established credible Zakat channels and governance, the broader Western charity sector still under-utilizes this market. Taking the example of Muslims in the UK and the U.S., the result shows that the gap isn’t demand; in fact, Muslim donors are generous and consistent with Jahangir Mohammed, founder and director, Ayaan Institute, pointing out that Muslim donations in the UK for international humanitarian charities stand at £1.5 billion with upto 40% of that amount comprising Zakat donations.

The problem thus lies on the supply side.

“When Muslim charities were first established in the United Kingdom, their efforts were largely directed overseas, focusing on humanitarian crises in Asia and Africa. This approach echoed the model of long-standing international NGOs such as Oxfam, and zakat distribution was typically confined to two of the eight categories set out in the Qur’an: the poor (fuqara) and the needy (masakin),” said Conor Murphy, chairman of Convert Muslim Foundation, a UK registered charity.

“In the past 15 years, however, the landscape has begun to change. A growing share of Zakat has been distributed locally to address hardship within British Muslim communities, from housing insecurity to food poverty. At the same time, some charities have broadened their interpretation of Zakat beyond immediate relief, using it to support converts to Islam (muallaf) and, more recently, to fund sustainable development initiatives. While these shifts remain the subject of debate among scholars, they mark an important evolution in how Muslim giving is practiced in Britain today,” he added.

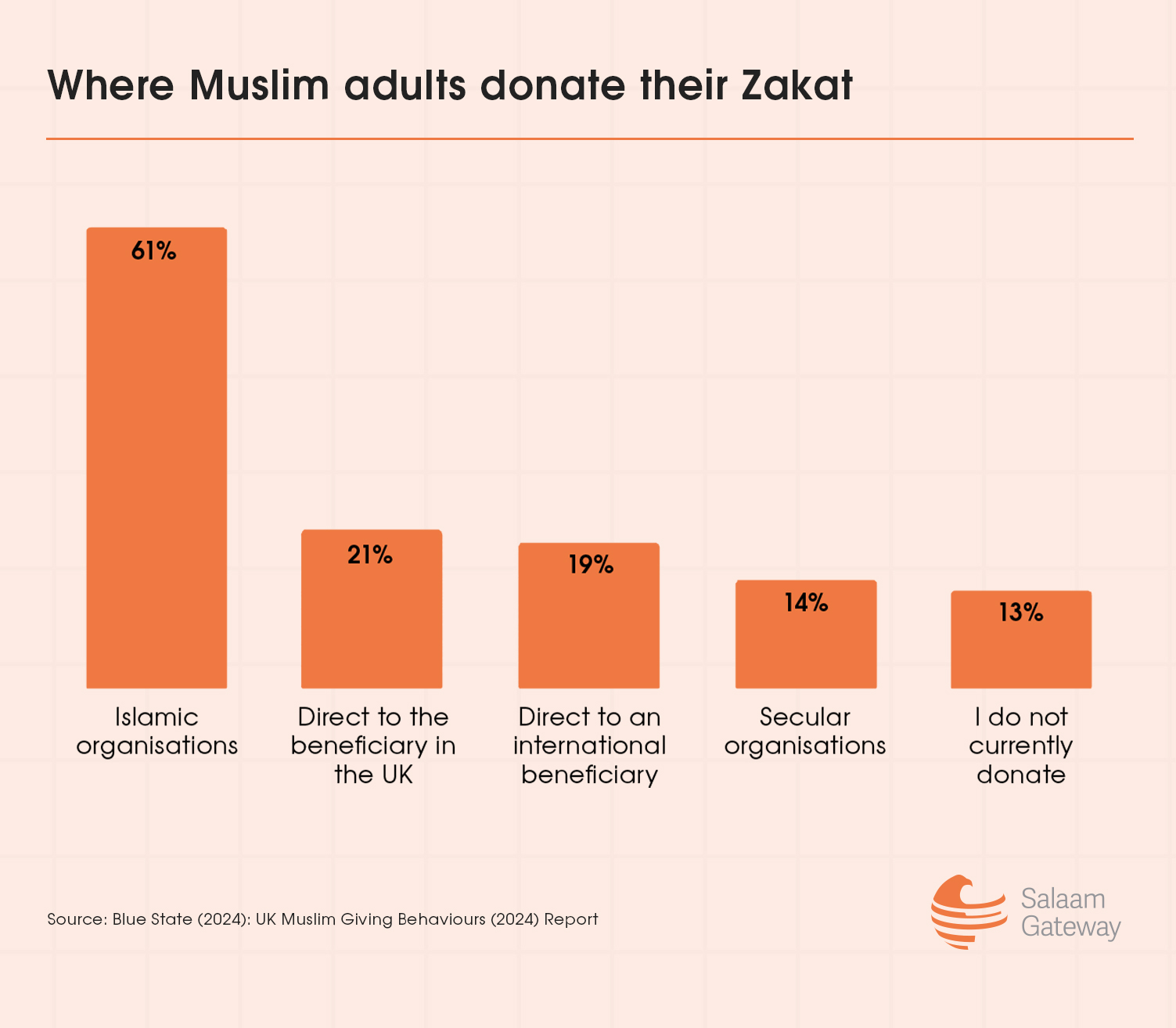

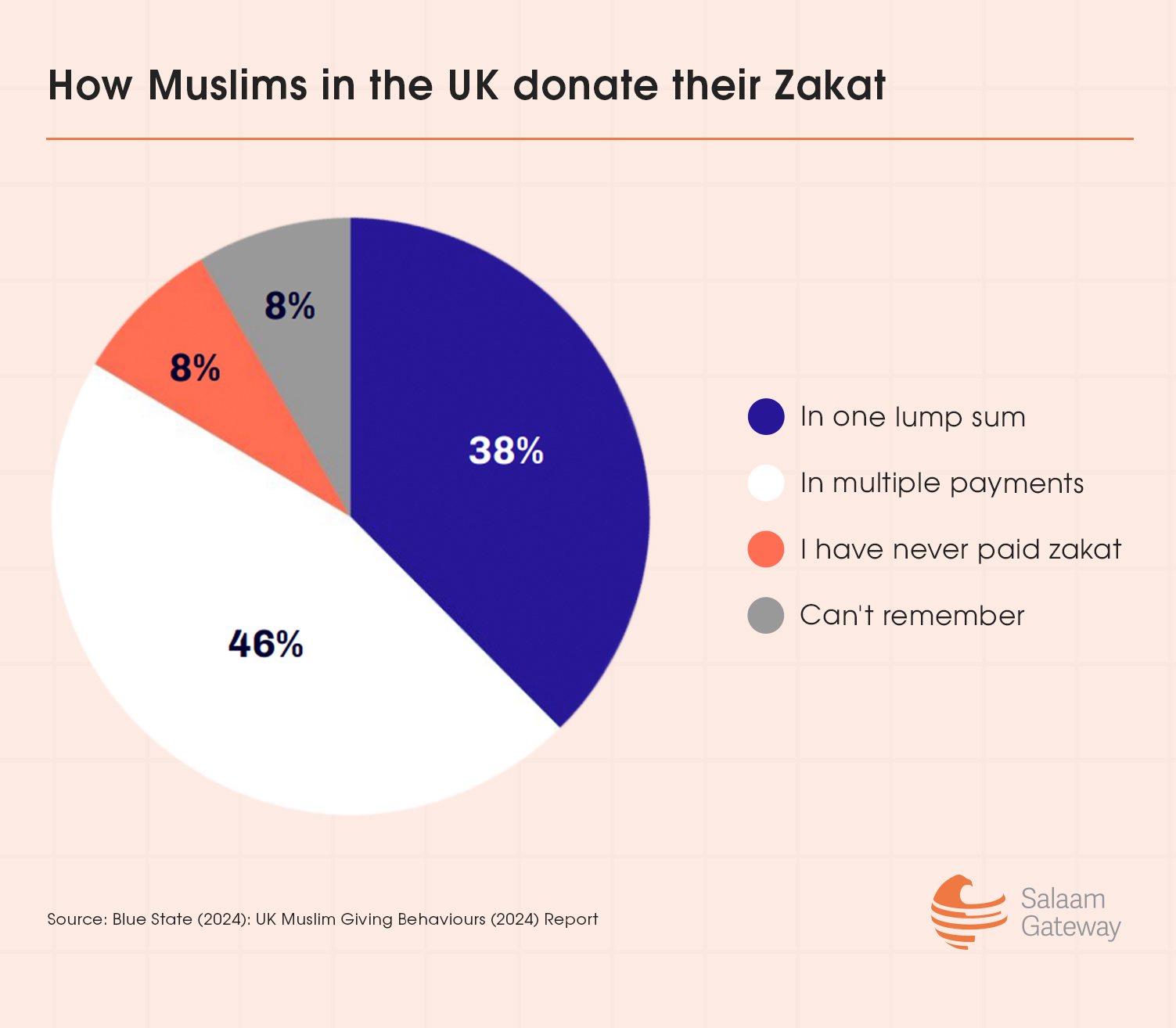

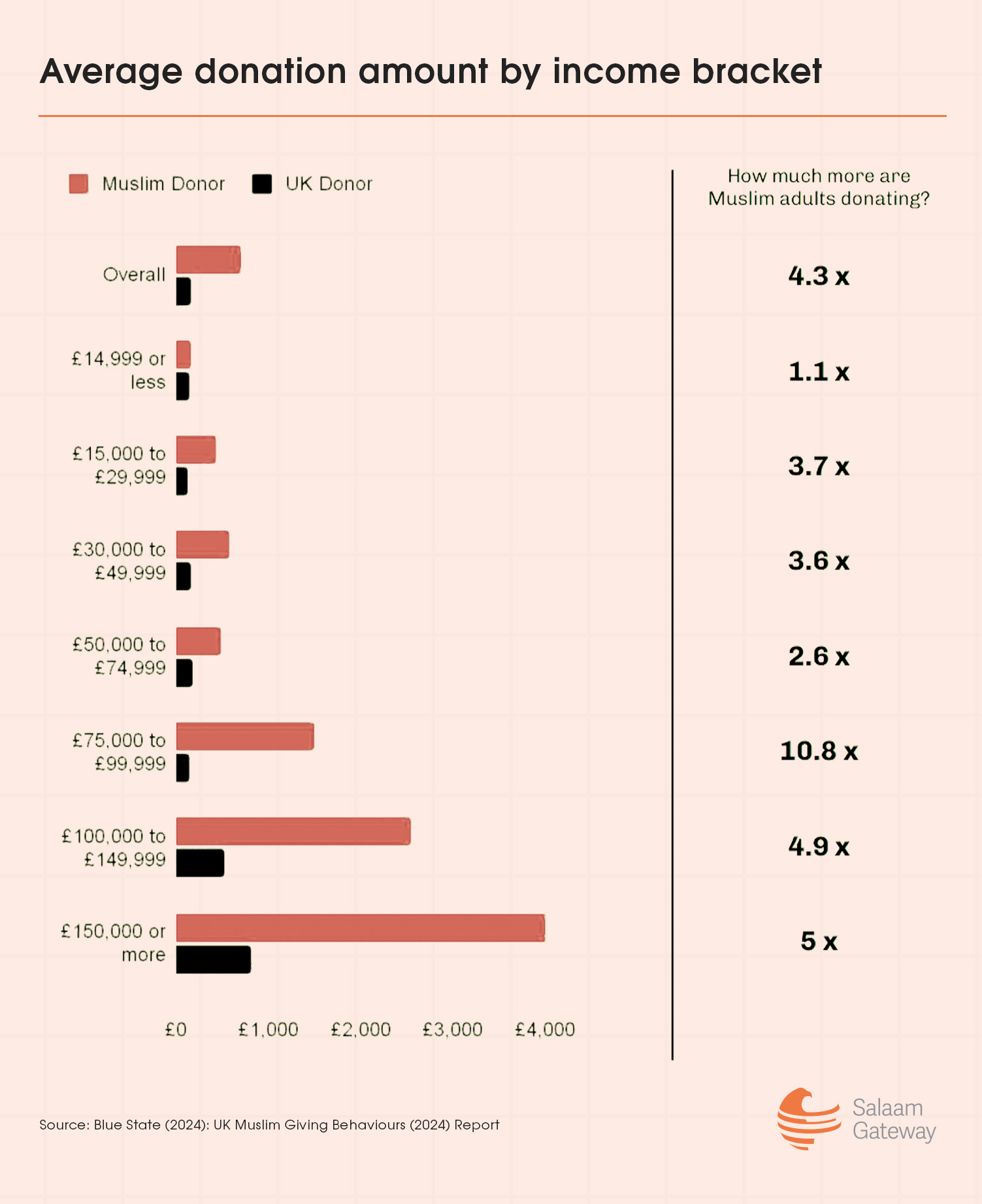

Blue State’s 2024 report shows most secular UK charities aren’t Zakat-ready, lacking ring-fenced funds, eligible programs, and clear communication. Yet the potential is huge: British Muslims give about £708 a year compared to £165 for others, but only 14% direct Zakat to secular groups. Half say they would if the process were clearer. In the U.S., the Muslim Philanthropy Initiative reveals a similar picture: around 70% of Muslims regularly pay Zakat, with annual giving worth billions.

A drop in the ocean

Some global organizations have gone well beyond Ramadan appeals, creating full systems to manage Zakat in line with Islamic guidelines. UNHCR’s Refugee Zakat Fund raised $14 million in 2024, reaching 474,000 people across 22 countries.

With Sadaqah included, the total reached $22 million, aiding nearly 872,000 people. UNICEF, in collaboration with the Islamic Development Bank, established the Global Muslim Philanthropy Fund for Children to channel Zakat into child-focused programs.

Meanwhile, UNRWA raised $41 million in 2024 through its Islamic Philanthropy program. Even secular bodies are joining in: the IFRC is now accredited to receive Zakat, and the IOM launched an Islamic Philanthropy Fund in 2025 to bring Zakat into mainstream humanitarian aid.

All of which begs the question: If donors and early movers exist, why isn’t Zakat ubiquitous across Western charities?

The barriers to Zakat in Western charities are mostly practical. Governance is the first: Zakat has strict rules, requiring ring-fenced accounts, Shariah oversight, and transparent reporting—systems that many charities lack, although the UNHCR has shown that they can be built.

Communication is another hurdle; research shows Muslims are open to giving Zakat to secular charities if they trust how funds will be used. Fundraising design also matters: Zakat is a year-round obligation, so donors expect calculators, tax-ready receipts, and clear Zakat-eligible programs—something faith-based NGOs already provide.

In the UK, Gift Aid adds complexity. While charities can claim the 25% top-up, scholars argue that it shouldn’t be considered Zakat, so most treat it separately. For donors, clarity on this point is essential to maintaining trust.

Bigger Picture

So, are Western charities truly maximizing the potential of Zakat? A handful certainly are, and they show it can work.

The first step is Shariah-aligned governance. Successful charities establish respected advisory boards and publish clear guidelines on which programs qualify for Zakat and how administrative costs are managed.

Agencies such as UNHCR, UNICEF’s Global Muslim Philanthropy Fund for Children, and the IFRC have all developed frameworks to demonstrate this alignment.

Zakat works best when it’s tightly managed and clearly explained. Leading organizations treat it as a separate, ring-fenced fund with transparent reporting and design programs that fit traditional categories, such as aid for the poor, debt relief, or family support.

The UK’s National Zakat Foundation shows how this can even tackle local hardship. Just as crucial is plain communication - when charities are upfront about rules, costs, and impact, Muslim donors are far more willing to give, even to secular organizations.

Many mainstream charities haven’t yet established the necessary structures—separate accounting, tailored programs, Shariah oversight, and culturally sensitive messaging—that enable Zakat to be implemented at scale. The irony is that the opportunity exists; it’s up to charities to step into it.

Muhammad Ali Bandial