European Commission's draft law aims to end corporate impunity

Will the new European Union (EU) rules minimise businesses’ destructive impact on workers, communities and the environment beyond the single market’s borders? The European Coalition for Corporate Justice (ECCJ) warns about the proposal’s flaws and exemptions.

The 2013 collapse of the Rana Plaza sewing workshops in Bangladesh, killing over 1,000 workers, and the 13-year-long legal battle of Nigerian farmers against the multi-national oil and gas giant Shell for lost wages, loss of livelihoods and contaminated land and water caused by oil spills, are simply two examples highlighting the adverse impacts of global supply chains on local communities and their difficulties to obtain justice.

In a bid to stop corporates shirking their sustainability and liability responsibilities, on 23 February 2022, the EU adopted a proposal that requires public and private sector companies registered in its territory to identify, prevent, end or mitigate adverse impacts of their activities on human rights and the environment.

“This proposal is a real game-changer in the way companies operate their business activities throughout their global supply chain,” EU Justice Commissioner Justice Didier Reynders said in a press statement about the directive that has been postponed three times since he first announced it in spring 2020.

“We can no longer turn a blind eye on what happens down our value chains. We need a shift in our economic model.”

The proposal

Under the new law, companies can be held liable for harms committed at home or abroad by their subsidiaries, contractors and suppliers. Their victims will have the opportunity to file lawsuits before EU courts.

It will apply to all EU limited liability companies with more than 500 employees and over €150 million ($165 million) in net turnover worldwide. In industries like agriculture and fashion where the risk of exploitation is higher, the draft covers companies with over 250 employees and a turnover of €40 million ($44 million).

While small and medium enterprises (SMEs) will be exempt, non-EU companies generating revenue in the single market exceeding these turnover thresholds are included. European Commission estimates indicate the proposal affects 13,000 EU companies and 4,000 non-EU companies.

National administrative authorities appointed by the member states will supervise the new rules and can impose fines in cases of non-compliance. In addition, companies with a turnover of €150 million ($165 million) must have a plan ensuring their business strategy is compatible with the Paris Agreement that limits global warming to 1.5°C.

The draft law is subject to approval by the European Parliament and, once adopted, will give member states two years to transpose the directive into national law.

The loopholes

“The Commission’s proposal is the first EU initiative of its kind and, that in itself is ground-breaking, but it fails to deliver on the potential,” said Claudia Saller, ECCJ director.

The ECCJ is the EU’s largest civil society network devoted to corporate accountability. It represents over 480 institutions from 17 countries and unites civil society, trade unions, consumer organisations and academics. The International Trade Union Confederation states 160 million (or 10%) of children worldwide are in child labour; 25 million people are in forced labour and there is an eight-year high in trade union and labour rights violations.

In light of this, Saller highlights various areas within the draft demanding rectification. Firstly, it only covers the EU’s largest corporations or about 0.2% of the region’s companies. By only covering large companies and some large ones in high-risk industries, the proposal falls short of international standards set out by the United Nations (UN) and the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) that target every business regardless of size.

Saller said while the proposal also outlines a new path to justice and compensation for exploited, traumatised, injured workers and communities, it doesn’t disburden victims to hold businesses accountable.

“It ignores serious legal hurdles that make lawsuits costly, lengthy, and complicated. The future law must be victim-based,” she said.

An ECCJ analysis of civil cases against EU companies for overseas human rights and environmental abuses revealed in some EU countries, the time limit for a party to bring a tort claim is as short as one year. This makes it challenging to bring in transnational cases on time.

In others, the limitation period begins to run even before harm is manifested. One example was the Pakistan-based Ali Enterprises factory fire in 2012 that claimed the lives of 258 people. Time limits prevented the victims from obtaining redress from the garment factory’s primary buyer, German discount retailer KiK.

Human rights exploitation in the fashion supply chain

A survey by EU-funded Fashion Checker highlights 93% of the 264 surveyed global fashion brands aren’t paying garment workers a living wage. Only four companies admitted they compensate at least some of their workers a living wage.

A living wage, recognised by the UN as a human right, is remuneration earned in a standard work-week of no more than 48 hours and must include enough to pay for food, water, housing, education, healthcare, transportation, clothing and some discretionary earnings, including savings for unexpected events.

In addition, the survey identified 60% of the firms questioned don’t adhere to any transparency obligations and just 46 companies (17%) disclose additional information about their supply chain, including facts about union representation in the workplaces.

The Swedish multi-national clothing company H&M exemplifies the many fashion companies that still made decent money despite the pandemic. For the year ending November 2020, the firm’s gross profit amounted to $9.6 million, corresponding to a 50% gross margin in local currency.

However, in the same year, workers at Indonesian H&M supplier PT. Sansan Saudaratex Jaya had to make ends meet with a monthly wage of €211.19 ($243.30). While the manufacturer with over 2,700 employees paid the lowest wages among the three Indonesian H&M suppliers listed in the Fashion Checker report, none of them reached the 2020 currency-converted living wage benchmark of €457.80 ($503.58).

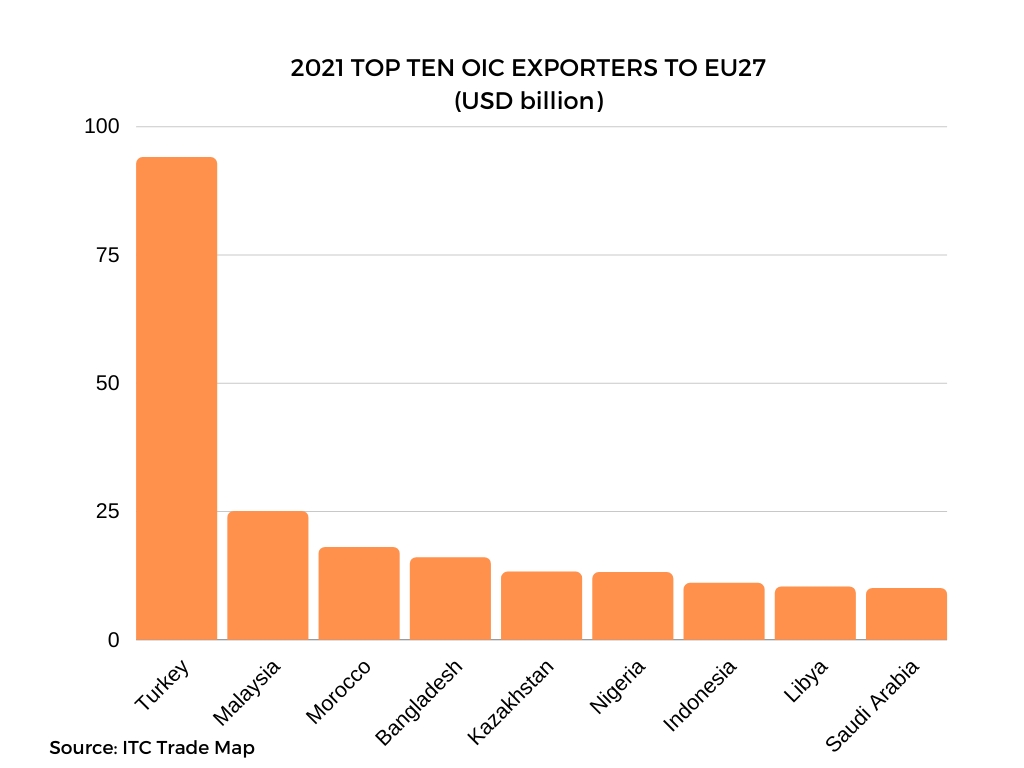

In 2021 the Organisation of the Islamic Co-operation (OIC) nations exported products worth $275 billion to the EU; a 3.6% year-on-year increase. The top suppliers were Turkey ($94 billion), Malaysia ($25 billion) and Morocco ($18 billion).

Saller said in future EU-based companies need to:

-

integrate corporate sustainability due diligence into policies;

-

identify actual or potential adverse human rights and environmental impacts;

-

prevent or mitigate potential impacts;

-

end or minimise actual impacts;

-

establish and maintain a complaints procedure;

-

monitor the effectiveness of the due diligence policy and measures

-

and publicly communicate on due diligence.

© SalaamGateway.com 2022. All Rights Reserved