How OIC nations are investing in food security

According to the World Food Program, food security is achieved when people have reliable access to sufficient, nutritious food. That might seem simple enough, but for decades, food security has meant emergency grain shipments in the 57-member Organisation of Islamic Cooperation (OIC).

Today, with climate shocks, volatile markets, and rising populations, it has become an even more pressing issue, making urgent investment essential.

The Global Food Security Index 2022 ranks most OIC states as "weak" or "very weak." While countries such as Bahrain, the UAE, and Uzbekistan are outliers with their progress, conditions have deteriorated at the other end in countries such as Somalia, Sudan, Syria, and Yemen between 2020 and 2022.

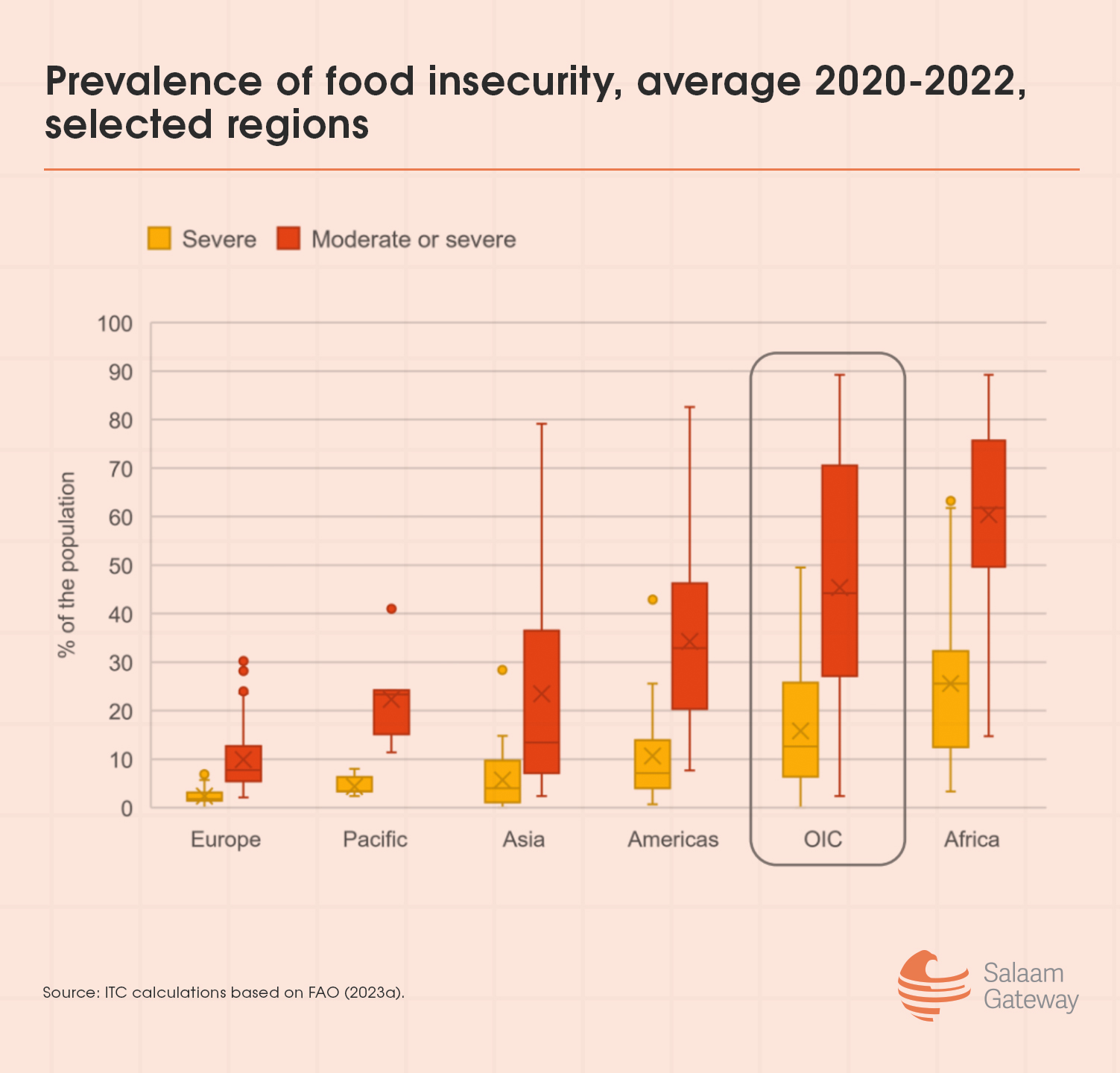

The FAO classifies 26 OIC countries as low-income food deficit states, and 22 require external assistance. Between 2020 and 2022, an average of 45% of the OIC's population faced moderate or severe food insecurity, with nearly half of the world's food crises occurring in OIC states.

Fragile systems on the brink of collapse

According to SESRIC's 2023 report, agriculture still provides livelihoods for millions and contributes more than 25% of GDP in 11 OIC member countries. But the region remains a net importer. In 2021, imports reached $292.9 billion, far outpacing exports at $188 billion, even as intra-OIC trade grew 85%.

The four pillars of food security reveal how exposed the region is. Domestic production has declined in many places, leaving states like Saudi Arabia, the UAE, and Jordan importing more than 90% of their cereals. Access to food is deeply uneven: food is affordable in the Gulf, but in sub-Saharan Africa, households spend more than their GDP-equivalent income on food, leaving them reliant on aid.

Malnutrition is entrenched, with nearly one in five children stunted, especially in Niger and Libya, where poor sanitation compounds the crisis. Stability is the weakest pillar: wars, droughts, floods, pandemics, and market shocks repeatedly push communities to the brink. In 2022, 172,000 people in OIC states were classified as facing famine, with millions more in emergency hunger.

Financing gaps in the agriculture chain

Agriculture in OIC countries remains severely underfinanced, receiving less than 5% of total credit. Only about 39% of farmers have access to finance or insurance, leaving smallholders vulnerable to shocks.

Some relief has come from multilateral financing. The Islamic Development Bank (IsDB) has committed $8 billion through its Food Security Response Program, while its trade finance arm, ITFC, channelled $1.75 billion into food and agriculture in 2024. But more is needed.

Sporadic investment responses

Before examining each country's investments, it's important to acknowledge that food security is a complex and vast area that translates to different areas of concern depending on each country's topography and specific requirements.

With financing channels under strain, OIC governments and institutions are turning to targeted investments across key sectors:

Water and land: The UAE's Bustanica vertical farm — a $40 million Emirates Crop One venture — now supplies Emirates Airlines, while a joint venture between Plenty Unlimited Inc., a U.S.–based indoor vertical farming startup, and Mawarid Holding Investment, a subsidiary of Alpha Dhabi Holding in the UAE, is to build five indoor farms across the GCC. Morocco's OCP Group has committed $13 billion (2023–27) to expand fertilizer capacity and develop green ammonia, backed by a €350 million AFD loan.

Agro-inputs and fertilizer: Morocco's OCP is ramping up exports across Africa, while Nigeria's Dangote Fertiliser plant, with a capacity of 3 million tonnes a year, has become a key supplier. Bangladesh's 2025/26 ITFC plan allocates $2.75 billion for petroleum and fertilizers.

Poultry and livestock: Qatar's 2024–30 Food Security Strategy focuses on poultry and dairy, while Egypt, with support from ITFC and the World Bank, is expanding feed and milling capacity.

Grain and logistics: Wheat imports remain unavoidable. Saudi Arabia's SALIC bought an 80% stake in Olam Agri for $1.78 billion in 2025, securing access to origination in Asia and Africa. The UAE's ADQ owns 45% of Louis Dreyfus Company, while Egypt has shifted to private wheat contracts, supported by $1.3 billion in ITFC financing.

Technology and insurance: The Islamic Corporation for the Insurance of Investment and Export Credit (ICIEC) issued $1.12 billion in guarantees for food-related trade between 2022 and 2024. The OIC's dedicated agency, IOFS, has proposed a $1 billion Grain Fund to pool reserves and invest in climate-resilient crops.

.jpg)

Progress is beset by gaps

Progress is tangible. But gaps remain. Tariffs and weak logistics hamper intra-OIC food trade. Efficient logistics and transport infrastructure are vital for lowering trade costs and ensuring predictable food imports. While OIC trading hubs benefit from advanced systems, many smaller economies face high costs due to weak networks.

Investing in transport corridors, alongside supportive trade agreements, could reduce costs, boost trade flows, and strengthen food security. Between now and 2027, several milestones will test these strategies: the SALIC–Olam Agri integration, OCP's green ammonia rollout, and the launch of the IOFS Grain Fund.

Muhammad Ali Bandial