Gaza crisis: How Palestinians are braving the employment fallout

For many Palestinians, the prospect of securing stable work now feels more distant than ever. After more than two years of relentless war in the Gaza Strip, local job opportunities have all but vanished, while access to the global labour market remains limited to a small number of highly qualified professionals.

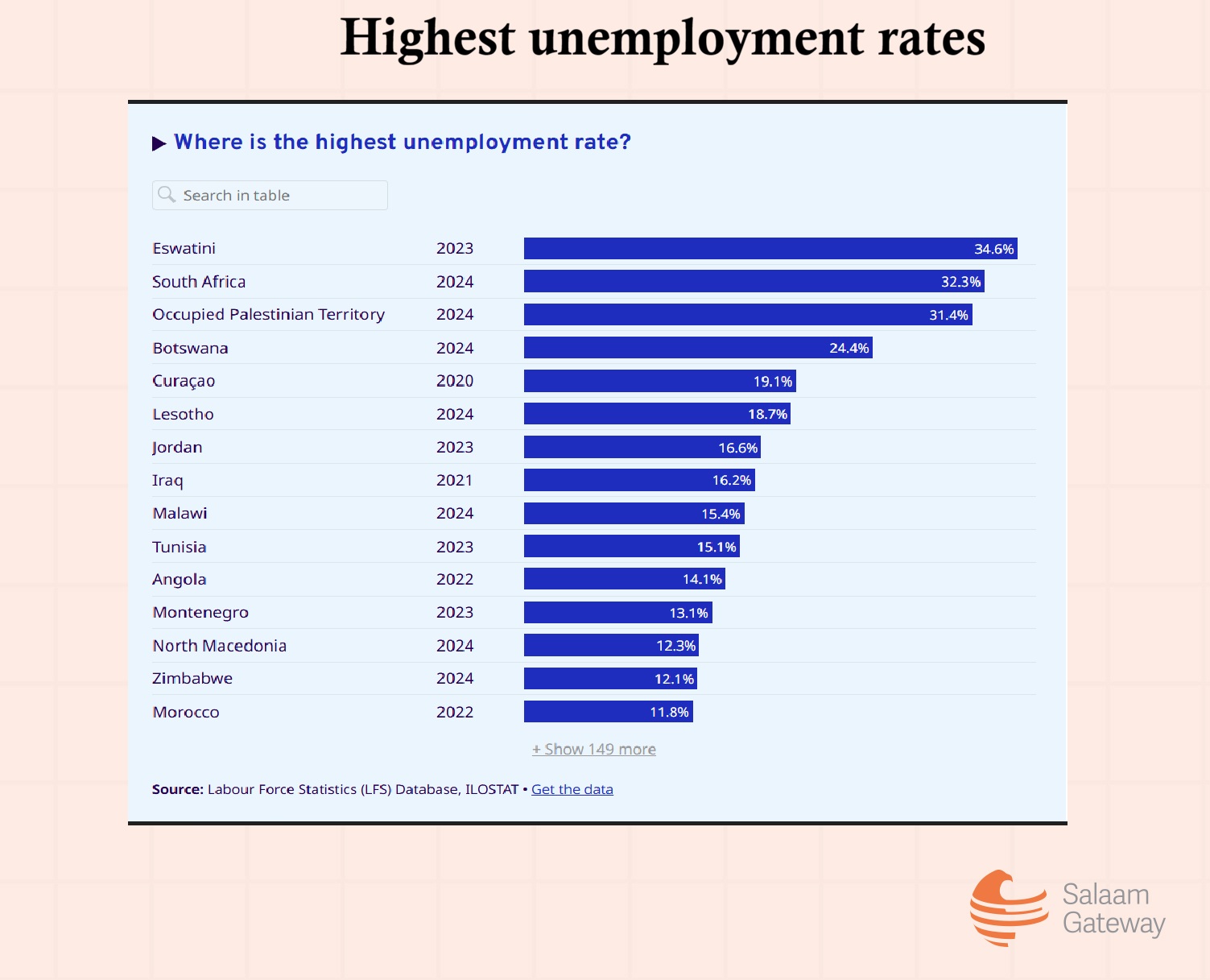

In the West Bank, nearly one-third of men and women were unemployed in early 2025, according to the International Labour Organization. In Gaza, the situation is far worse, with government data showing unemployment soaring to almost 68% by the end of 2024.

The war has wiped out most sources of income. Local organisations have shut down, and the commercial sector - shops, bakeries, and small businesses - has been nearly destroyed. The collapse has affected both seasoned professionals and a generation of young people graduating in devastation.

“Although Palestinians are incredibly skilled - they’re amongst the highest educated in the region with an almost 20-year tradition of monetising skills online - they face additional challenges,” Kathrine Nicolaisen, founder and CEO of Olives & Heather, a remote-first, Palestinian social-impact marketing agency, tells Salaam Gateway.

Those who completed their studies between 2023 and 2026 are entering a labour market that barely exists.

“That is four graduating cohorts, each numbering in the thousands. Imagine all these young people entering a devastated job market,” Farah Alejil, humanitarian programs officer at Gaza-based NGO AlAnqaa Association for Community Development tells Salaam Gateway.

Alejil graduated just months before the war began. “The public sector is non-operational, the private sector is barely functioning, and while the international job market remains active, it demands exceptionally high qualifications and at least five years of experience,” she adds.

Battling the perception of instability

One of the most persistent obstacles is perception. Employers - particularly international ones - often hesitate to invest in Palestinian talent due to assumptions about instability, reliability, and infrastructure.

“Sure, during active war Palestinians and especially Gazans will not be working at 100% capacity, but they’re extremely flexible and motivated, and will find ways to make things work,” says Nicolaisen.

Alejil says this reluctance is widespread in remote hiring. “Foreign employers think twice before hiring people from Gaza because of concerns around financial transfers, productivity, and their ability to deliver work consistently - simply because they’re based in Gaza.”

“That said, some employers are willing to take the risk, and when they do, the impact can be significant. Even if just 20 people are hired out of a thousand, those 20 often go on to train and employ others, creating a ripple effect that supports entire households.”

Infrastructure gap

Even when jobs are theoretically available, the basic conditions needed to work remotely are often missing. Many students completed their education entirely online during the war, yet lack access to stable electricity, Internet, or professional training in how to find and sustain remote work.

“Over the past two years, Internet access has been repeatedly cut off. Electricity is rarely available,” says Alejil.

“I personally have an external power line, but many people don’t even have an electricity connection. How can remote workers function under these conditions?”

The disruption has stalled the careers of experienced professionals as well. Senior developers who once juggled multiple international clients now find themselves with one - or none. Long-standing contracts have been terminated, and entire outsourcing branches shut down.

“Some youth-led workspaces exist, supported by external funding, but there are thousands of graduates, and these spaces can only accommodate 20 to 30 people at a time,” adds Alejil.

“Even then, the Internet is not always stable. Internet access is beyond our control - the lines are largely supplied from the Israeli side and can be cut off from all of Gaza at any time.”

Nicolaisen points to the extraordinary measures many Palestinian remote workers take just to stay online - combining solar panels, car batteries, and eSims to generate power and secure Internet access.

Payment barriers

Getting paid remains another formidable challenge. Financial restrictions and exclusion from international aid initiatives continue to isolate Palestinian workers from the global economy.

“Even initiatives launched to serve refugees and displaced communities exclude Palestine,” says Nicolaisen. “All of these factors combined makes it very hard for Palestinians to access the international job market.”

She adds that basic survival needs - housing, safety, and mental health - place an enormous burden on freelancers trying to maintain professional commitments amid ongoing trauma.

Alejil echoes this reality. “For entrepreneurs, private loans are nearly impossible to obtain, and even professionals working for international organisations struggle to receive their salaries. Western Union is blocked throughout Gaza, and wire transfers are extremely difficult.”

As a result of these challenges, a lot of digital employees have been let go by their employers over the past two years, according to Nicolaisen.

“Rather than adjusting, they decided to cut ties and even close down whole outsourcing branches.”

Training, placement, and local solutions

Despite the scale of the crisis, some organisations are working to rebuild pathways into employment.

Olives & Heather collaborates with local and international tech startups and ecosystem builders - including Gaza Sky Geeks, the Palestinian IT Association, and social enterprise BuildPalestine - to train and place Palestinian marketers and designers.

BuildPalestine has intensified its efforts, recently launching a $1.2 million fundraising campaign aimed at tripling the number of impact-driven businesses it supports - from 25 today to 65 enterprises by 2028 - signalling a longer-term commitment to economic resilience.

Complementing these initiatives, educational programmes such as Axsos Academy, a Palestinian coding bootcamp, equips talent with the skills needed for online work, while recruiters including Foras, MENA Alliances, and TAP play a critical role in connecting Palestinians to job opportunities.

Axsos Academy recently partnered with US-based NGO HEAL Palestine to launch 50 fully funded tech scholarships for youth from Gaza, offering a tangible pathway to skills development and employment amid the ongoing crisis.

Nicolaisen believes the tech sector offers the most immediate potential for job creation in Palestine.

“The tech sector is already contributing 4% to the Palestinian economy, and the potential is infinite,” she says.

“All Palestinians and Gazans need to start making an income and rebuild their lives is a laptop and an Internet connection.”

At the local level, organisations like AlAnqaa Association are often more effective than large international NGOs, according to Alejil.

“They hire from within the community - people with experience, though not necessarily elite qualifications - bringing in fresh graduates, supporting and training them, and gradually increasing their responsibilities.”

“Today, we have 72 employees, which is a significant achievement for a local organisation,” she says. “About 12 are permanent full-time staff, and the rest part-time.”

AlAnqaa recently launched a mobile physiotherapy outreach programme, employing newly graduated physiotherapists to provide care to injured citizens in their homes. The organisation is also preparing to establish a workspace to support both local employment and online work in Gaza.

A workforce in waiting

The crisis facing Palestinian workers is not a shortage of talent, ambition, or work ethic - it is a crisis of access, infrastructure, and imagination.

Palestinians have spent decades building skills for the digital economy, only to be locked out at a time they need it most.

Yet within this bleak landscape, small but significant interventions are proving that employment is possible when flexibility and trust are prioritised.

From community-led NGOs to remote-first tech initiatives, these efforts offer a blueprint for how global employers, donors, and policymakers can move beyond sympathy toward meaningful inclusion.