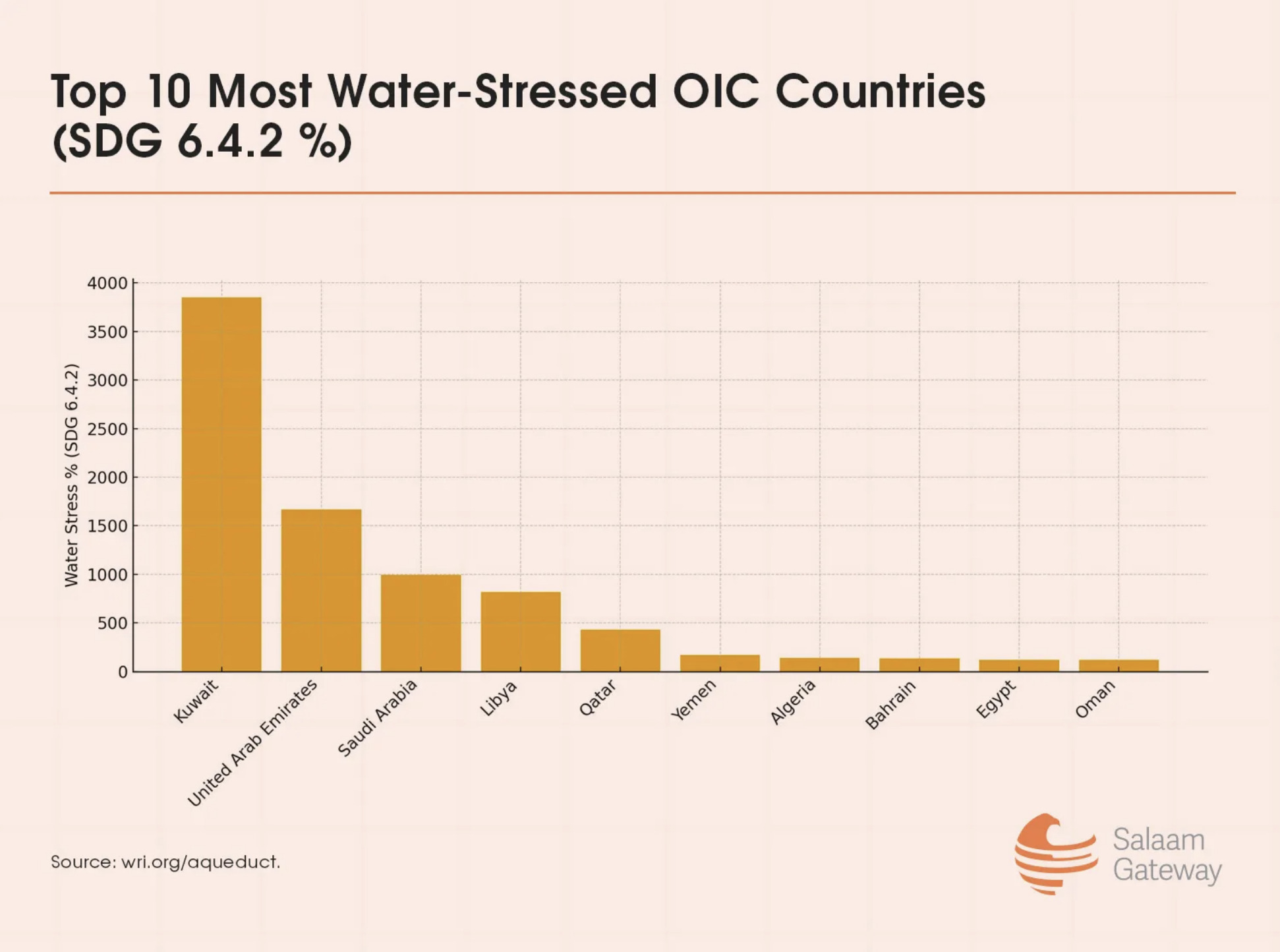

Ten most water-stressed OIC countries

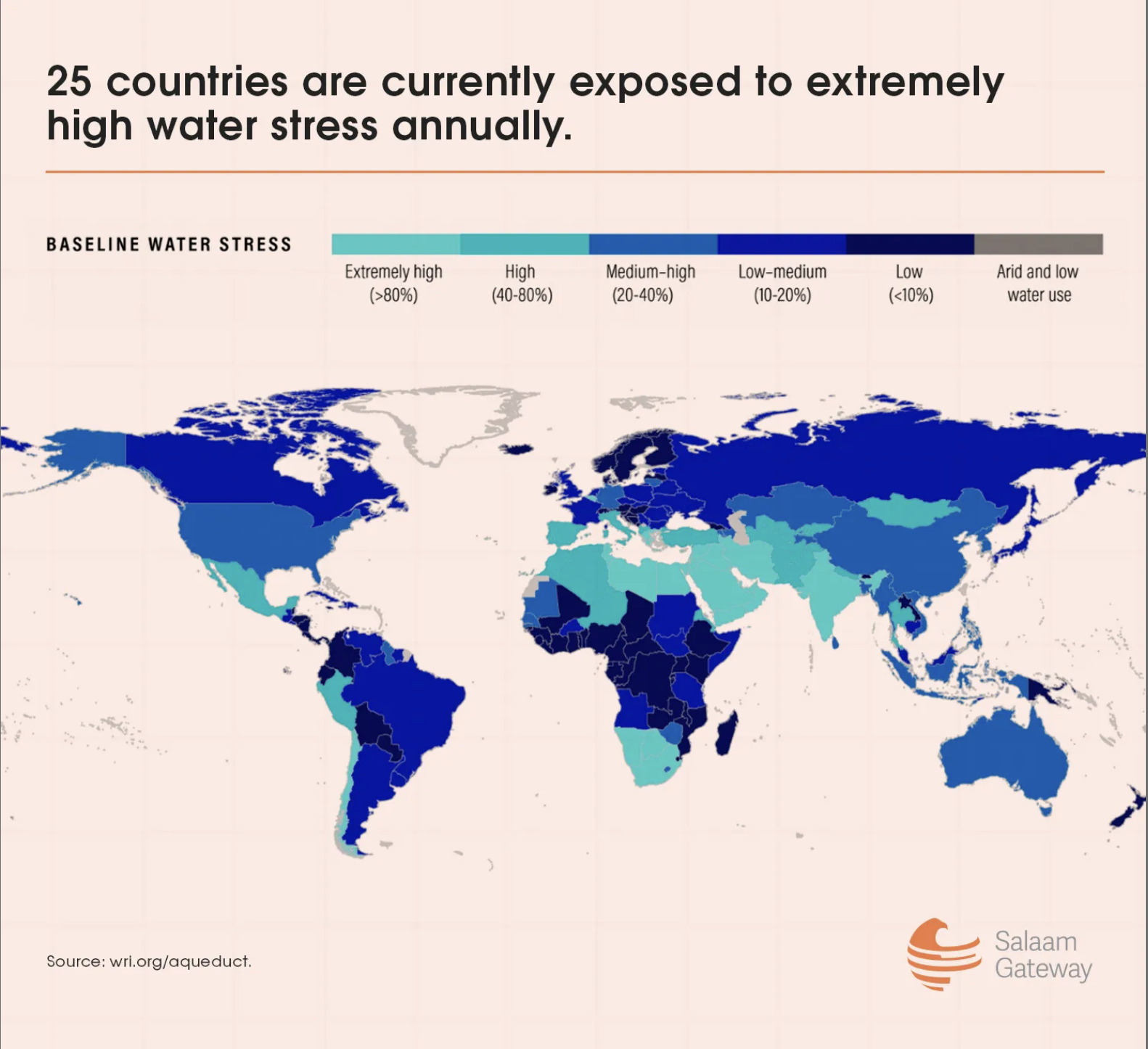

Water scarcity is affecting countries across the world and is becoming increasingly front of mind with governments.

Global water demand has more than doubled since 1960, driven by population growth and industrialization. Water stress, defined as the share of renewable water withdrawn, reveals how tight the balance has become: “high” stress means at least 40% of resources are used yearly, while “extreme” stress means 80% or more.

According to the latest figures from WRI’s Aqueduct Water Risk Atlas, 25 nations, home to roughly a quarter of the world’s population, are under extreme water pressure.

Around four billion people globally experience high water stress for at least one month annually, highlighting how widespread the shortage has become.

Muslim countries feature prominently in the list of the most water-stressed countries. Across the 57 member states of the Organisation of Islamic Cooperation (OIC), many countries now rely on costly stopgaps like desalination and fossil groundwater.

This article explores the ten most water-stressed OIC countries, ranked by the UN’s SDG 6.4.2 indicator, which measures freshwater withdrawals as a percentage of available renewable resources. Anything above 25% signals severe stress; above 100% means withdrawals exceed natural supply.

Kuwait

With just 4.83 cubic meters of renewable water per person annually, Kuwait’s natural supply is effectively zero. By contrast, the Falkenmark index defines 500 m³ as the threshold for “absolute scarcity.” Kuwait’s staggering 3,851% water stress score means its withdrawals are almost forty times higher than its renewable supply. All this demand is met through desalination, powered by oil and gas. While desalination guarantees taps do not run dry, it comes with high costs that threaten fragile Gulf ecosystems.

United Arab Emirates

The United Arab Emirates (UAE) is close behind, with a stress score of 1,667%. Like Kuwait, it sits on almost no renewable water - just 15.57 m³ per capita. Desalination has enabled this desert country to grow rapidly, but the risks are mounting. The UAE has invested in recycling wastewater and promoting water efficiency in agriculture, but the reality is that its natural endowment cannot support its population without permanent technological intervention.

Saudi Arabia

Saudi Arabia withdraws water at 993% of its renewable supply. With per-capita availability of just 71 m³, it falls deep into absolute scarcity.

For decades, the kingdom pursued self-sufficiency in wheat and other crops by pumping ancient non-renewable aquifers. That policy drained reserves at unsustainable rates and was eventually abandoned, but its legacy endures: vast tracts of desert now bear the scars of empty wells.

Today, Saudi Arabia is the world’s largest producer of desalinated water, and food security has shifted from local production to imports. But even desalination has limits, both environmental and financial. Rising demand, climate change, and energy transition pressures make the kingdom’s water future precarious.

Libya

In Libya, water stress stands at 817%, with just 105 m³ per capita of renewable supply. The country relies almost entirely on the Great Man-Made River Project, a colossal pipeline system that taps into fossil aquifers beneath the Sahara. Built in the 1980s, it once symbolized national pride and self-reliance. Today, the system is crumbling under the strain of war, neglect, and over-extraction.

Qatar

Qatar, despite its wealth, faces water stress of 431%. Per-capita renewable water stands at just 20.85 m³, among the lowest in the world. Like its Gulf neighbors, it has built an economy reliant on desalination, but with additional vulnerability: agriculture consumes a disproportionate share of water, even as local production remains limited.

Yemen

With a stress score of 170% and just 74 m³ per person, Yemenis face chronic shortages even in the best of times. Conflict has destroyed water infrastructure, leaving millions without safe access.

Algeria

Algeria records water stress of 138%. With 276 m³ per person, it is in absolute scarcity, worsened by erratic rainfall and climate variability. Agriculture consumes more than 70% of withdrawals, making the country especially vulnerable to drought. Algeria has invested in desalination and dams, but these measures are playing catch-up against demand that already outstrips renewable supply.

Bahrain

Bahrain faces water stress of 134% with per-capita renewable availability of just 74 m³. Historically reliant on underground aquifers, Bahrain has seen those reserves salinized by seawater intrusion. Today, desalination provides most drinking water, but the ecological costs of brine discharge weigh heavily on the surrounding marine environment.

Egypt

Even with the Nile, Egypt, with a population of over 110 million, is experiencing water stress. Its renewable supply amounts to just 584 m³ per person. Egypt’s stress score is 117%, meaning it withdraws more than the river can sustainably provide. Rapid population growth, upstream pressures from Ethiopia’s Grand Renaissance Dam, and climate change-induced variability in Nile flows are intensifying the strain.

Oman

Rounding out the list is Oman, with stress at 117% and just 290 m³ per person. The country’s traditional aflaj irrigation systems, recognized as UNESCO heritage, have long allowed Omanis to live with scarce water.

But modern pressures - urban growth, rising consumption, and industrial demand - are pushing the system to breaking point. Oman has turned to desalination, yet its water balance remains fragile.

Looking ahead

Even under an optimistic climate scenario where global temperatures rise only 1.3°C to 2.4°C (2.3 °F to 4.3 °F) by 2100, another billion people could be living under extremely high water stress by 2050. Over the same period, global water demand is forecast to climb 20–25%, and the number of watersheds with highly unpredictable year-to-year supplies is expected to grow by about 19%.

The numbers make clear the need for multi-layered solutions, including better governance, reduced agricultural demand, investment in recycling and efficiency, and regional cooperation on shared rivers and aquifers.

The OIC, as a bloc, has an opportunity to lead in fostering the political cooperation that is often lacking in transboundary water management. Without that, the region risks turning water from a source of life into a trigger for conflict.

Muhammad Ali Bandial